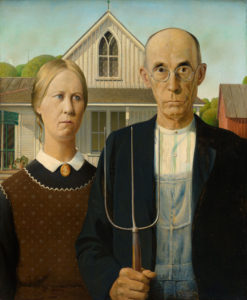

It is common for an appraiser to find themselves serving a client that has very strong ideas about the identity or historical provenance or characteristics of their item or collection. Sometimes these ideas or beliefs are founded in family lore or some other long-accepted tradition or reason. However, it is the appraiser’s job to apply critical thinking to whittle things down to ‘just the facts.’

It’s probably not hard to imagine how uncomfortable that position can be, especially when faced with a client for whom their story means the world. They’ll wonder why you’re so concerned or skeptical over seemingly mundane background facts. After all, great grandma said George Washington once tripped over this!

It’s probably not hard to imagine how uncomfortable that position can be, especially when faced with a client for whom their story means the world. They’ll wonder why you’re so concerned or skeptical over seemingly mundane background facts. After all, great grandma said George Washington once tripped over this!

One of my professional advantages is that I bring university training in historiography to my appraisal practice. The times when this training helps me shed new light on an item by identifying some hitherto unknown or underappreciated characteristic are truly momentous and among the most rewarding for me personally. Of course, clients are happy as clams if the detail adds value, but more often than not, they’re just as thrilled with the intellectual value I’ve identified. After all, there’s a lot of satisfaction in adding a footnote to history.

Now, this is not possible without me applying critical thinking, defined as the objective analysis and evaluation of an issue in order to form a judgment, to my historiographical formulae.

This means that I must view items dispassionately when I am valuing them for monetary worth. Instead of focusing on the good, brightest and most immediately attractive aspects, I must give equal attention to the flaws, the cracks, the chips, the repairs, the patina, the wear, the missing parts, the broken parts, the incompleteness, the anachronisms, etc.

The more significant a piece purports to be – historically or monetarily, the more sternly I must focus on the detractive or negative aspects. A thorough and honest valuation is the goal, so an item must stand up to the most rigorous and skeptical standards. This is the hard part because, like everyone else, I’d rather be celebrating greatness!

That’s not to say there isn’t nuance in this job. Often enough, an examination points toward the inconclusive on one or more points. All is not necessarily lost, but additional work must be done. For very significant items, the appraisal itself could be scuttled at this moment. At this point, I begin to search for why something may be the way it is. Has it been tampered with over the intervening years? Can we tell if the tampering innocently or maliciously executed? Was the tampering done to obscure another fact? Was the tampering done to enhance the item?

That’s not to say there isn’t nuance in this job. Often enough, an examination points toward the inconclusive on one or more points. All is not necessarily lost, but additional work must be done. For very significant items, the appraisal itself could be scuttled at this moment. At this point, I begin to search for why something may be the way it is. Has it been tampered with over the intervening years? Can we tell if the tampering innocently or maliciously executed? Was the tampering done to obscure another fact? Was the tampering done to enhance the item?

And, of course, the most important question I must answer in terms of the appraisal for monetary value is: does this impact value one way or another?

The answer may not always be to the owner’s liking, but the goal remains to get us closer to the honest truth.